I have been doing a little remodeling to an old garage that is next to my home in California. This is a 1935 era house that I recently purchased, needing a “bit” of fixes and upgrades. Many years ago I was a small time general building contractor doing upgrades, small additions and repairs. Kind of a licensed “handyman” sort of thing with a small crew of permanent helpers and a wide variety of subcontractors. The nature of this work resulted in my being “adequate” in many trades for small projects. A bit of a “Jack of All Trades, Master of None.” Even though I haven’t been in that business for many years I have maintained my license in an “inactive” state.

Since the garage upgrade is a small project I elected to do most of the work myself. I am now puzzling over adding some ceiling lights and a few plugs so I can use the space as my woodshop. My first instinct was to just do the work based upon my experience – but decided it might be fun to get more inquisitive and investigate new practices, materials and changes to the National Electric Code (NEC). Checking the new electrical codes reveals a surprising number of changes over the past few decades, and I find many new items on the store shelves. I am researching things as I go along, finding many new items in the stores – especially new tools and parts.

I would like to discuss a couple of the issues that I have been pondering – not so much because of the technical aspects of the topic, but more interestingly because of the nature of the arguments among “qualified” tradesmen (licensed electricians or experienced tradesmen). I find their approach to finding “truth” and “good solutions” to be interesting, and not a little scary. I selected my examples because of ease of understanding the issues, but I find similar problems exist in almost all technical fields.

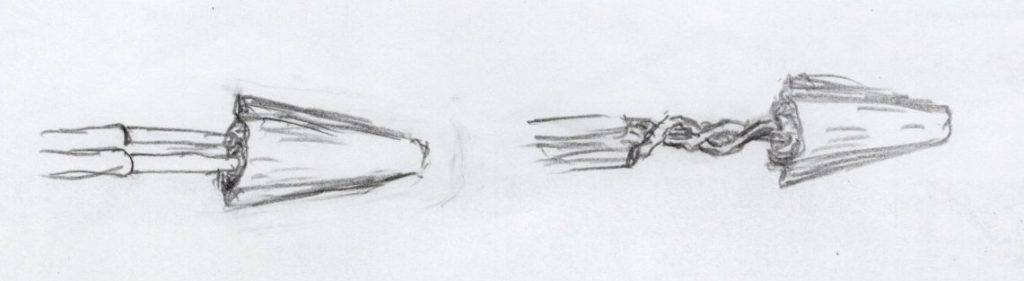

A couple of the issues that I have heard argued over the years is how to make a proper wire junction and connection to an electrical device (e.g., a switch). Wire nuts are a popular means of joining wires within electrical boxes because they are quick, easy and meet code. Wire nuts are plastic devices containing a coiled spring that is “screwed” (by hand) onto two or more wires – making a solid electrical and physical connection between the wires. They come in various sizes to accommodate different sizes and number of wires to be joined. The main argument that hear about them is whether or the wires go straight into wire nut, or are they supposed to be twisted together first. Sort of like this:

Most electricians that I talk to insist that it is necessary to first tightly twist the wires together and then install the plastic connector. Not only do they take this position, but the electricians I know are pretty derogatory about “lazy, incompetent” people taking dangerous “short cuts” by not twisting the wires. This is actually a pretty big deal because of the connection isn’t tight enough it can overheat because of resistance or arcing, resulting in a fire – or if over tightened it can damage the wires, leading to broken wires and all sorts of problems, including fire.

The NEC is almost silent on this topic. It says, “Conductors shall be spliced or joined with splicing devices identified for the use.” While that sounds pretty vague, it actually means a lot – it means a device that is “rated” for the use, meaning it is designed for the application and listed by a testing agency such as UL AND that it is installed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (that were used as the basis for the UL testing). So, it has to be an acceptable device for the use, and it has to be used properly in accordance with specific, written, manufacturer’s instructions. In several cases that I could track down, the manufacturers instructions indicated that the wires should NOT to be twisted before use, but instead straight wires are inserted – the device does the correct twisting. A few manufacturers state that either approach is acceptable, but give no means of knowing how to determine if they are twisted properly. My guess is that they left that there to make old timers happy, but actually intend the wires to be inserted and then twisted.

There is no way to determine correct twisting in the field because it depends upon unobservable and untestable practices. This is one of the reasons that the devices have been designed like they are, if the specific directions are followed there is a large body of testing and verification to support the claim of a correct installation. Depending upon the “skill” of the installer is extremely dangerous. As a safety engineer, I far prefer a designed and tested solution to one that depends upon personal skill.

Another example of an electrical mystery has to do with connecting wires to devices (switches, receptacles, etc.) Most 15 Amp receptacles used in houses are provided with two means of connecting wires to them. There are usually four screws on the sides for power and one screw for the ground wire. Sometimes there are also four little holes in the back where wires can be inserted to make the connections. “Real” electricians once again claim that only lazy and unprofessional installers use the holes, they claim that the only “professional” installation is using the screws. There was actually a problem when these screwless connectors were developed because they were designed for 12 gauge wire. Since 12g wire (larger diameter) and 14g wire (smaller diameter) are used in residential applications, sometimes the manufacturer’s instructions were not followed specifying that ONLY 12g wire be used in the back connections, resulting in instances where the connections were not tight enough. That problem has been solved by making the holes smaller, they can no longer be used with the larger wire and therefore the connections are tight enough with the 14g wire. That was a problem with relying upon instructions rather than design to get good results.

The electricians that I have talked to, and read about in electrical chat rooms, say that side-wiring is best. However, side wiring requires a lot of skill, is prone to several errors, and isn’t testable because it depends upon the skill of the individual installer. It requires the wire to be cut the correct length (not an obvious thing to do), needs to be bent to the correct shape (without a guide or means of measuring), needs to be installed in the correct direction (easily mistaken), and the wire has to be property located under the head of the terminal screw (difficult to do or inspect). And then, it has to be properly tightened (not too tight or too loose). In addition, for some reason that I can’t figure out, the terminal screws are designed to make it almost impossible to get the wire loop into the available space. All of this opens many avenues for error, and eventual overheating and fire.

Clearly a better solution is needed, and that seems to be back wiring using straight, unbent, wires, that have a good solid connection feature. This can be achieved with property manufactured spring devices that are designed and tested (as it the case for all major brands), a back wired approach with hand tightened screws (good, but require torque measurements), or the newer back fed devices with a lever clamp. Once again, the “professionals” seem to be working off of old “wives tales” (industry wisdom) rather than science and engineering. I find that to often be the case, many in the building profession claim that they know best, that the manufacturers don’t know what they are talking about, so the professionals don’t follow the instructions – feeling so much superior to the companies that design, test and verify their designs. I know that once in a while the designers make mistakes, and I know that sometimes installations that work at first fail over time, but I also know that they are a much better chance at getting it right than the typical trades-person who learned his trade from the “good old boys” in the profession. Things are often more complicated than they appear – which is why there is so much effort made in testing and verifying designs and products.

The points that I am trying to make aren’t that “professional electricians” don’t know what they are talking about, or are somehow incompetent. I am hoping to point out that there is a tendency for people, even very experienced professionals, to make assumptions about how things work (or should work), therefore

“fixing” problems incorrectly, often inadvertently making the problems worse. There is often a conflict between how we imagine things work resulted in our making up a “better” solution that in the end causes problems attributed to “human error.” The error often isn’t so much in doing something “wrong” (as in mistakenly), rather it is often due to mistakes in understand how things actually work. A couple of recent airplane crashes can be attributed to that sort of “error,” an error in understanding how the flight controls work resulted in improper use, resulting in crashed airliners.